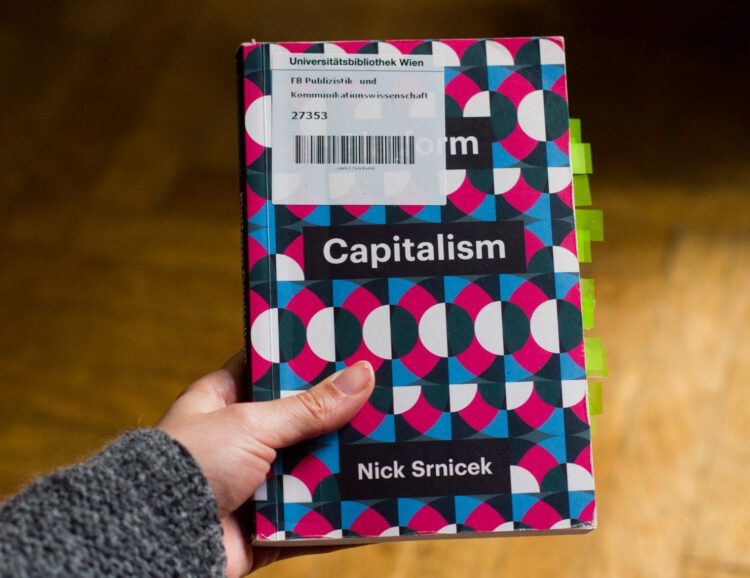

Dieses Buch, das fast als Essay durchgeht (es ist in großer Schrift und mit vielen Abständen gesetzt und hat ohne Anhang trotzdem nur knappe 130 Seiten), habe ich halb als Uni- und halb als Interessenslektüre gelesen, und obwohl es von 2017 ist und sich seitdem schon wieder gefühlt das halbe Web verändert hat, ist es eine super Einführung ins Thema.

Srnicek ordnet den derzeitigen Techplattform-Boom historisch ein, und zwar als eine logische Folge auf den industriellen Niedergang in den großen Nachkriegs-Industrieländern, darauf folgender Austeritätspolitilk, generell immer neoliberalerer governance und, nach der Krise von 2008, sehr niedrigen Zinsen. Letztere sind ein wesentlicher Faktor für das Wachstum der Techbranche:

„lean platforms are entirely reliant on a vast mania of surplus capital. The investment in tech start-ups today is less an alternative to the centrality of finance and more an expression of it. Just like the original tech boom, it was initiated and sustained by a loose monetary policy and by large amounts of capital seeking higher returns.“

Seite 120

Es sei nicht unwahrscheinlich, dass die Blase platzt (genau wie dot-com um die Jahrtausendwende, zu der Srnicek auch sonst einige Parallelen sieht), denn:

„growth in the lean platform sector is premised on expectations of future profits rahter than on actual profits. The hope is that the low margin business of taxis will eventually pay off once Uber has gained a monopoly position. Until these firms reach monopoly status (and possibly even then), their profitability appears to be generated solely by the removal of costs and the lowering of wages and not by anything substantial.“

Seite 87

Dieser Hang zum (quasi) unkontrollierbaren Monopol hat nicht nur auf die ausgebeuteten gig workers schlimme Auswirkungen, sondern auf die Gesellschaft als Ganzes:

„At their pinnacle, they have prominence over manufacturing, lgistics, and design, by providing the basic landscape upon which the rest of the industry operates. They have enabled a shift from products to services in a variety of new industries, leading some to declare that the age of ownership is over. Let us be clear, though: this is not the end of ownership, but rather the concentration of ownership. Pieties about an ‚age of access‘ are just empty rhetoric that obsucres the realitites of the situation. Likewise, while lean platforms have aimed to be virutally asset-less, the most significant platforms are all building large infrastructures and spending significant amounts of money to purchase other companies and to invest in their own capacities. Far from being mere owners of information, these companies are becoming owners of the infrastructures of society. Hence the monopolistic tendencies of these platforms must be taken into account in any analysis of their effects on the broader economy“

Seite 92

Als Lösungsweg sieht Srnicek einerseits Regulierungspolitik, andererseits auch Plattformen, die von der Allgemeinheit kontrolliert werden. Mir persönlich scheint nix davon besonders realistisch, aber außer auf das Platzen der Blase (das angesichts der negativen Folgen der Plattformisierung des Webs in jedem Fall zu weit weg ist) zu warten fällt mir leider auch keine bessere Lösung ein…

Nick Srnicek: Platform Capitalism. Polity Press, 2017. 171 Seiten.

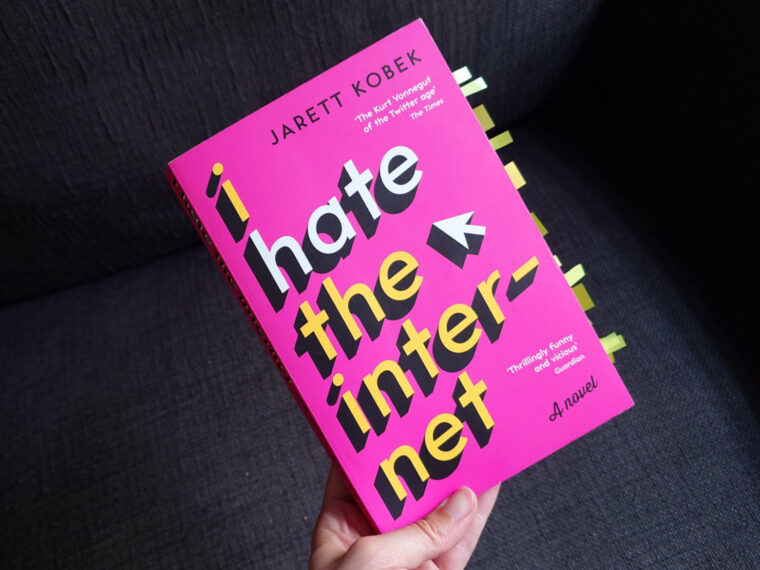

Btw, neulich habe ich auf Twitter entdeckt, dass Michael Seeman (@mspro) seine Dissertation fertiggestellt hat und sie bald als Buch erscheint: Die Macht der Plattformen. Politik in Zeiten der Internetgiganten werde ich mir auf jeden Fall zulegen, wahrscheinlich finden sich darin noch viel mehr spannende Analysen zum Thema.

Hi, ich bin Jana. Seit 2009 veröffentliche ich hier wöchentlich Rezepte, Reiseberichte, Restaurantempfehlungen (meistens in Wien), Linktipps und alles, was ich sonst noch spannend finde. Ich arbeite als Redakteurin bei futurezone.at, als freie Audio-/Kulinarikjournalistin und Sketchnoterin. Lies mehr über mich und die Zuckerbäckerei auf der

Hi, ich bin Jana. Seit 2009 veröffentliche ich hier wöchentlich Rezepte, Reiseberichte, Restaurantempfehlungen (meistens in Wien), Linktipps und alles, was ich sonst noch spannend finde. Ich arbeite als Redakteurin bei futurezone.at, als freie Audio-/Kulinarikjournalistin und Sketchnoterin. Lies mehr über mich und die Zuckerbäckerei auf der

Über den Tellerrand

Über den Tellerrand Bücher

Bücher Zuckersüß

Zuckersüß

2 Comments

Comments are closed.